How Troye Sivan Redefines Queer Visibility in Pop Music

Exploring how Troye Sivan’s career reflects the evolving landscape of queer representation in music.

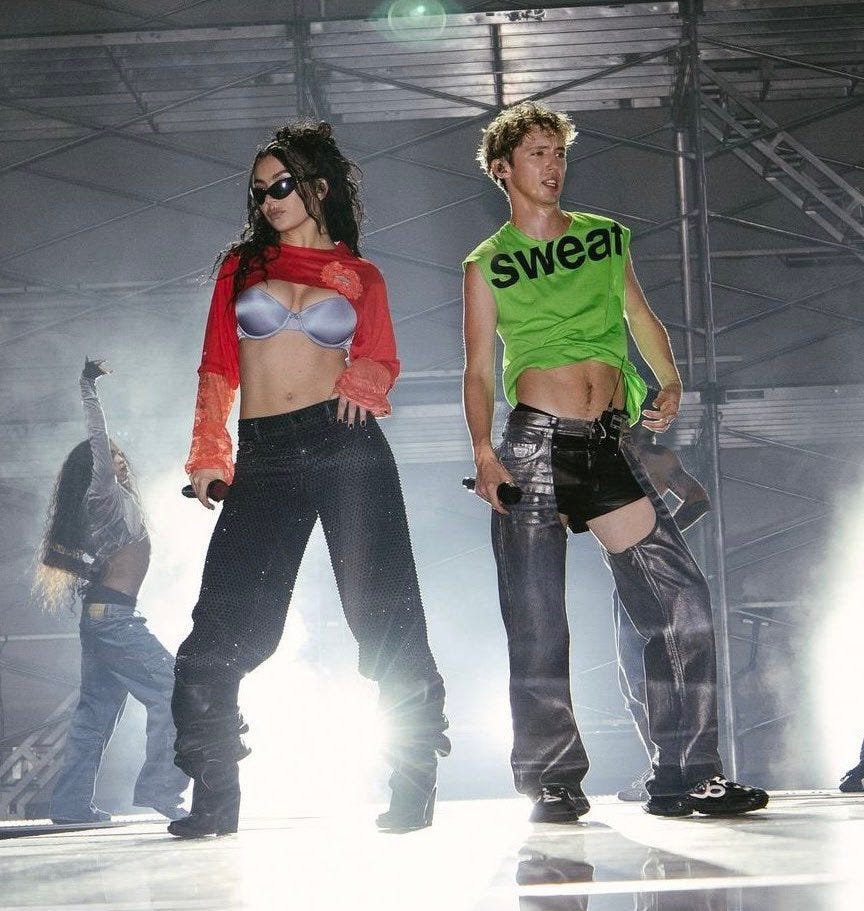

Last fall I spent an evening in the 300 level nosebleeds of the United Center in Chicago. It was an arena full of popper fumes, body odor, hyper pop music, an abyss of lime green, and the electricity of the LGBTQ+ community. And it was of course the Sweat Tour — ever heard of it?

The Sweat Tour, co-headlined by Charli XCX and Troye Sivan, was more than just a concert. It was a cultural milestone, a space where queerness wasn’t just present—it was embraced at a arena-filling scale worldwide. This was every gay person’s Met Gala, birthday, Super Bowl, (maybe even funeral) and Christmas combined.

During the middle of Troye Sivan’s sets, I was in trance, covered in goosebumps all the way in the 300s. It later got me thinking: has something like this ever happened before? When has an openly young and queer pop star headlined an arena world tour AND didn’t have to hide their identity from their career? It felt as if history was writing itself right in front of me.

In typical me-fashion, I thought what does it mean to be an LGBTQ+ popstar today vs back then? Do we live in a world today where achieved mainstream success is possible without homophobic setbacks?

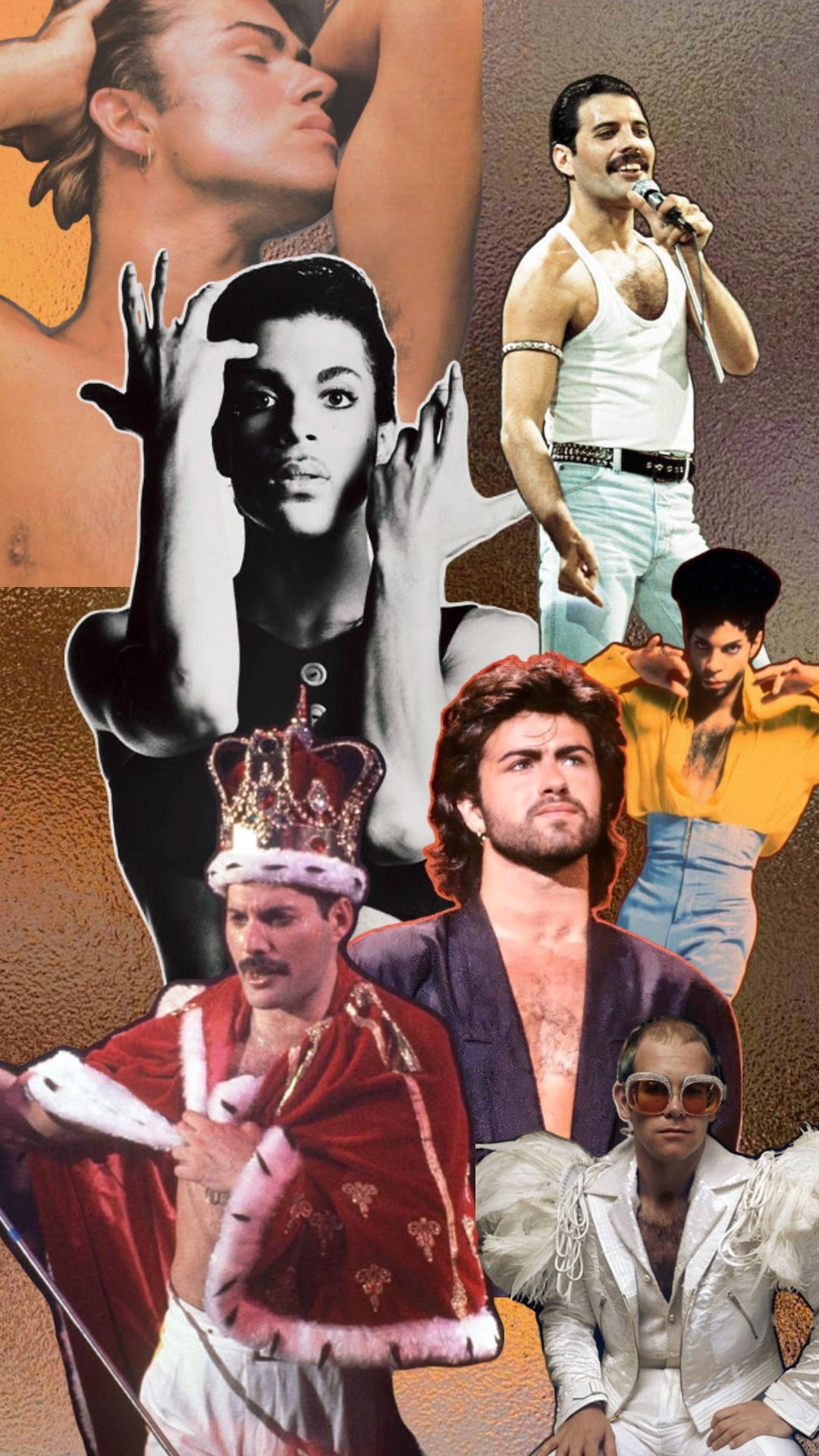

Gay and queer artists have always been in the music industry, duh. But, let’s rewind a few decades. Think of icons like Prince, Elton John, Freddie Mercury, Lance Bass of *NSYNC, Ricky Martin, and George Michael, who all hid their sexuality and identity during (or parts of) their career out of fear and safety. They lived in a time where being gay meant being ostracized. These gay men fought the rumor mill by presenting straight in public heterosexual relationships.

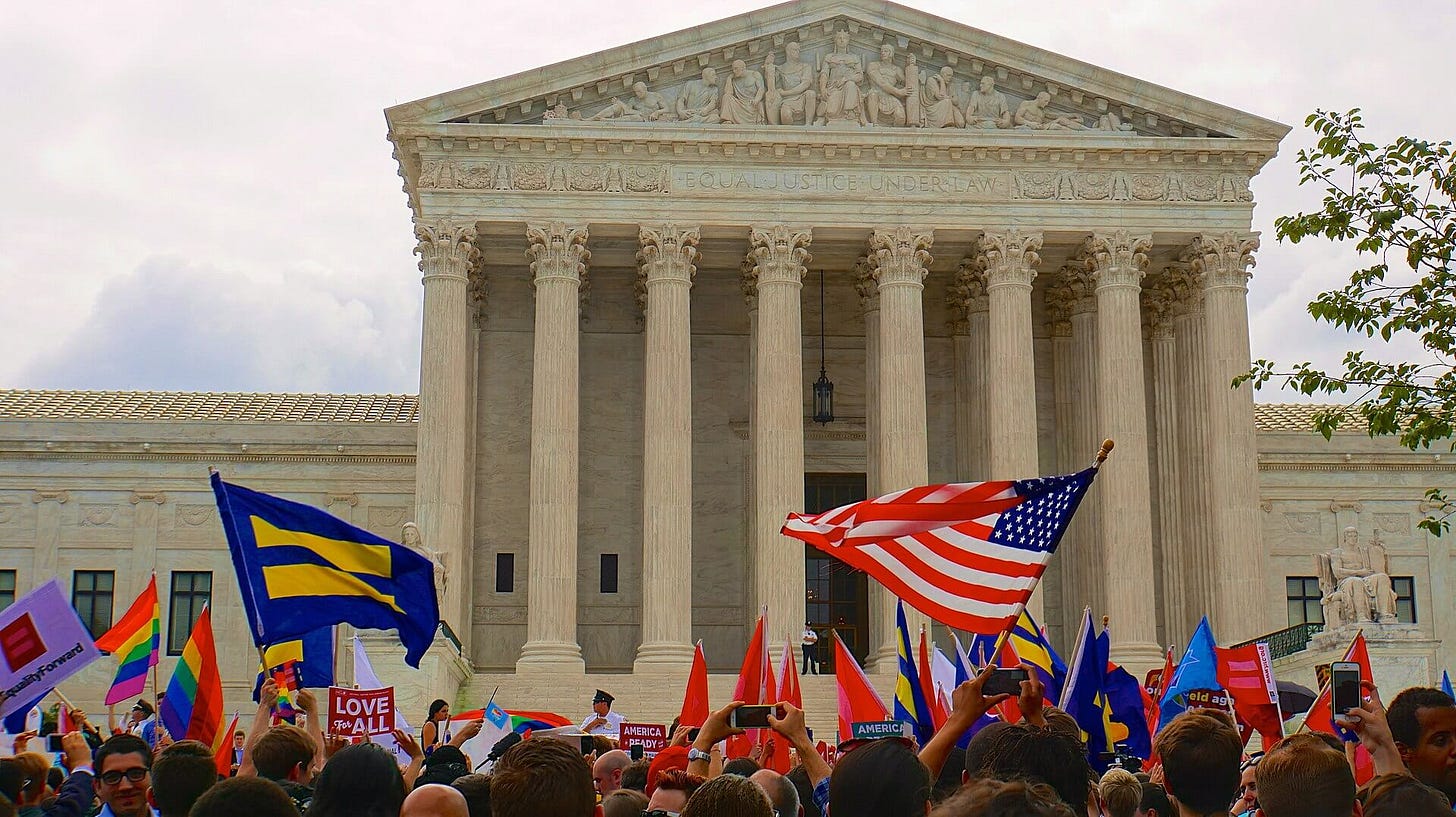

Homophobia has shaped recent and past U.S. history and culture, yet its impact is often overlooked. From the events of the Stonewall riots, the HIV / AIDS epidemic, transgender bans, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”, and Obergefell v. Hodges (and the current rumblings of it being overturned), there has been a consistent and complex fight for LGBTQ+ liberation.

The Lavender Scare from the 60s-70s silenced, hunted, and punished queer individuals and couples for existing. Over 300,000 gay men died in the AIDS epidemic, including Mercury himself. Roughly 2-3% of individuals identified as LGBTQ+ in the 1980s. The number has risen to seven percent today not because the water is turning us gay, but because queer people have always existed. AND we are finally starting to exist safely in a world today.

Pivoting from my original thoughts, the bigger question lies –how ready is the world to embrace LGBTQ+ pop stars and queer culture in the mainstream media? If not, how do we continue to fight the good fight?

While no single artist carries this responsibility alone, Troye Sivan’s career feels especially important today. His popularity is bubbling beneath mega-mainstream status, and I anticipate a bright future for him and his influence.

Unlike past queer icons, Troye Sivan never had to hide his sexuality to protect his career. Troye built his career on queerness from the very start. And the start being his teenage years. That’s more than just progress—it’s a cultural shift.

Almost a decade ago, Troye Sivan dropped his debut album, Blue Neighborhood (2015), a queer coming-of-age, 2010s timepiece dealing with first love, closeted heartbreak, coming out trauma, and self discovery. Blue Neighborhood follows his coming out journey like so many queer youth face growing up – the hidden discoveries of authenticity, the weight of unrequited love, and the complexity of finding oneself amidst heartbreak in a heteronormative world.

His sophomore album, Bloom (2018), follow up EP, In A Dream (2020), and slew of single releases carved his footing further into the pop landscape in the later 2010s into the 2020s. While navigating the highs and lows of gay adulthood, nothing is taboo for Troye (as it should be) – embracing sexual intimacy in title track “Bloom”, “10/10”, and “My, My, My”, longing for a lost lover on “Easy” and “Could Cry Just Thinking About You”, or processing the past in “Seventeen” and “Rager Teenager.”

Troye’s platform and career continues to evolve today. He released his third studio album, Something to Give Each Other (2023), which is critically argued to be his best and most mature release yet. With two Grammy nominations, Something to Give Each Other is a very, VERY gay album. The lead single, “Rush”, is a sexy, sweaty club anthem that intently hits like a whiff of poppers. The “One of Your Girls”’ music video debuted Troye in drag while giving a lap dance to Ross Lynch. He’s undeniably cool and full of mojo in songs like “Silly”, “In My Room”, and “Honey”.

Also, his performer side stepped up in this album cycle. If you saw me practicing the Got Me Started choreography, no you didn’t. His Sweat Tour choreography was responsible for the goosebumps I mentioned earlier. The boy’s got swagger and it’s even brainwashing straight women. Check TikTok if you think I'm exaggerating.

Sivan’s visibility is impactful, especially for young queer people. Personally speaking, Blue Neighborhood served as a lifeboat during my teenage coming out phase. His following projects dive into the transition from closeted adolescence into queer adulthood. It’s multilayered in euphoric healing, sexual exploration, overcoming past lives, and dabbles with the depths of young love.

It’s a privilege to come out alongside an artist I share an identity with and the same experiences as. How I navigated my identity and coming out journey would be very different if I lived in a different decade with little to no mainstream representation.

These experiences may seem mundane (or “weird” / alluring to R*publicans), but erasing these identities negatively impacts vulnerable identities.

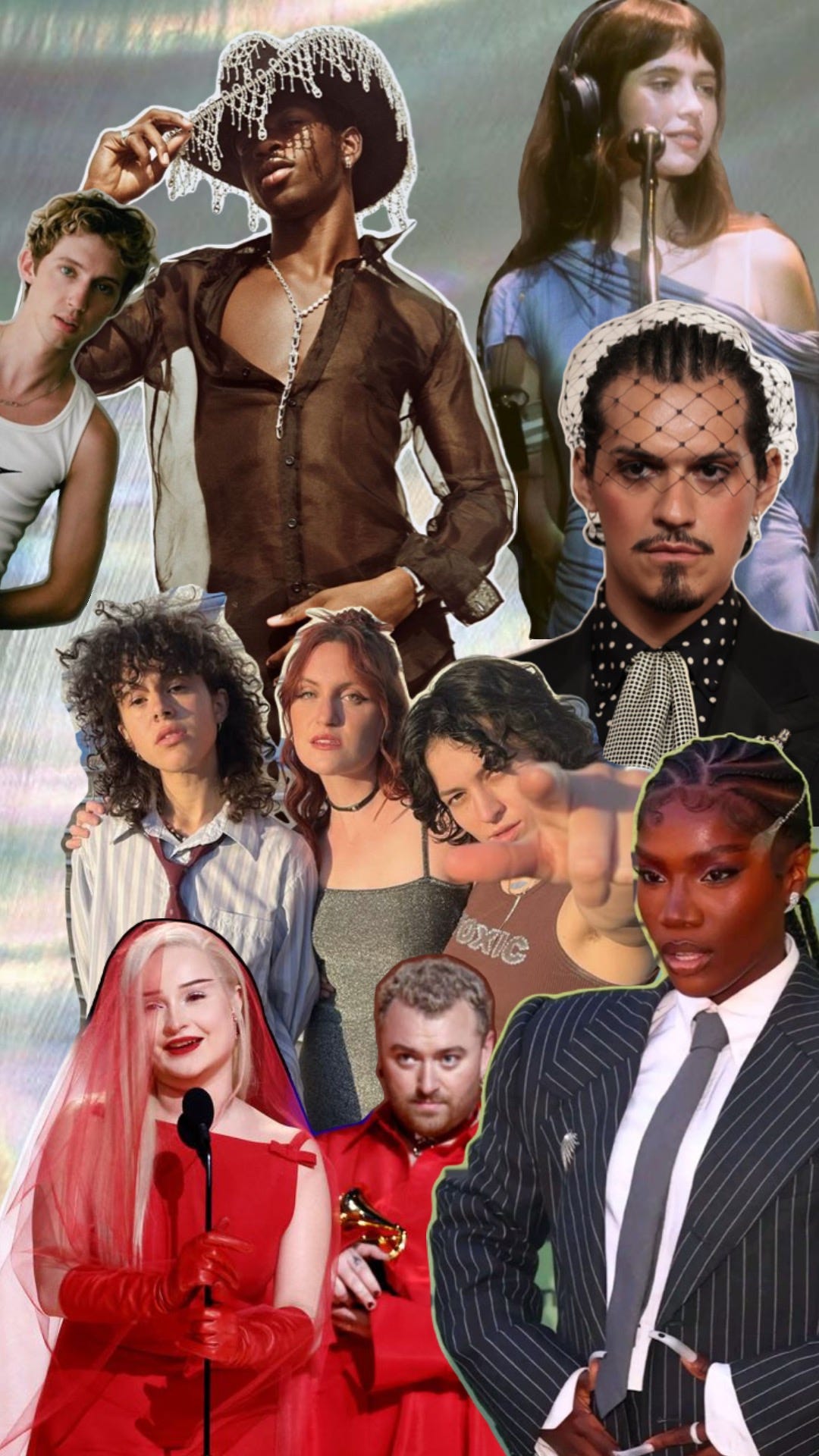

Yet, LGBTQ+ recognition amongst artists is making waves today – Lil Nas X, Doechii, Tyler the Creator are shattering systemic racism and homophobia in their respective genres. Trans artists are trailblazing the music industry led by Kim Petr

as, Ethel Cain, and Sasha Allen. Queer women like Chappell Roan, Janelle Monet and Brandie Carlile are collecting Grammy recognitions like Thanos’s infinity stones.

Troye Sivan is part of an army of LGBTQ+ artists. Whether they know they’re working together or not, the representation across all identities under the queer umbrella is something to not go up against. Systemic homophobia, your days are numbers.

Something that makes Troye different from other LGBTQ+ artists are the direct ties to Charli XCX. The past year was a breakthrough for Charli XCX and her critically acclaimed album brat (2024). The album shifted and molded popular culture like play doh, and the Sweat Tour slam dunked on its cultural climax. To be associated with her is a huge win.

Troye’s nearly 10 year career proves he’s deserving of commercial success. Troye’s momentum from the Sweat Tour positions him for greater artistic, critical, and political influence. It could be working with producers like Max Martin to aim for a Billboard Number One record or a Grammy win. Maybe a collaboration with a relevant queer artist can infiltrate the Spotify and Apple Music charts. Imagine a Clairo, Lil Nas X, or Chappell Roan collab. It would go triple platinum in my apartment.

Whether it’s earning a #1 hit, pushing the envelope with visual art, or creating platforms for even more LGBTQ+ artists, Troye Sivan is living proof that queer pop stardom isn’t just possible—it’s the future. My last question remains though: how far can we take it?

👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻

YESSSSS LOVE